In 2016, Berna Heyman testified before a U.S. Senate committee about her personal experience with sudden and dramatic increases in drug prices. She was forced to switch drugs to treat her chronic genetic disease, which was not the ideal option for her.

“The only reason I changed was the cost,” Berna testified. Her health had been stable while taking the drug Syprine, which removes excess copper in people with Wilson disease (WD) to prevent potentially fatal poisoning. “My doctor and I made the change only under duress.”

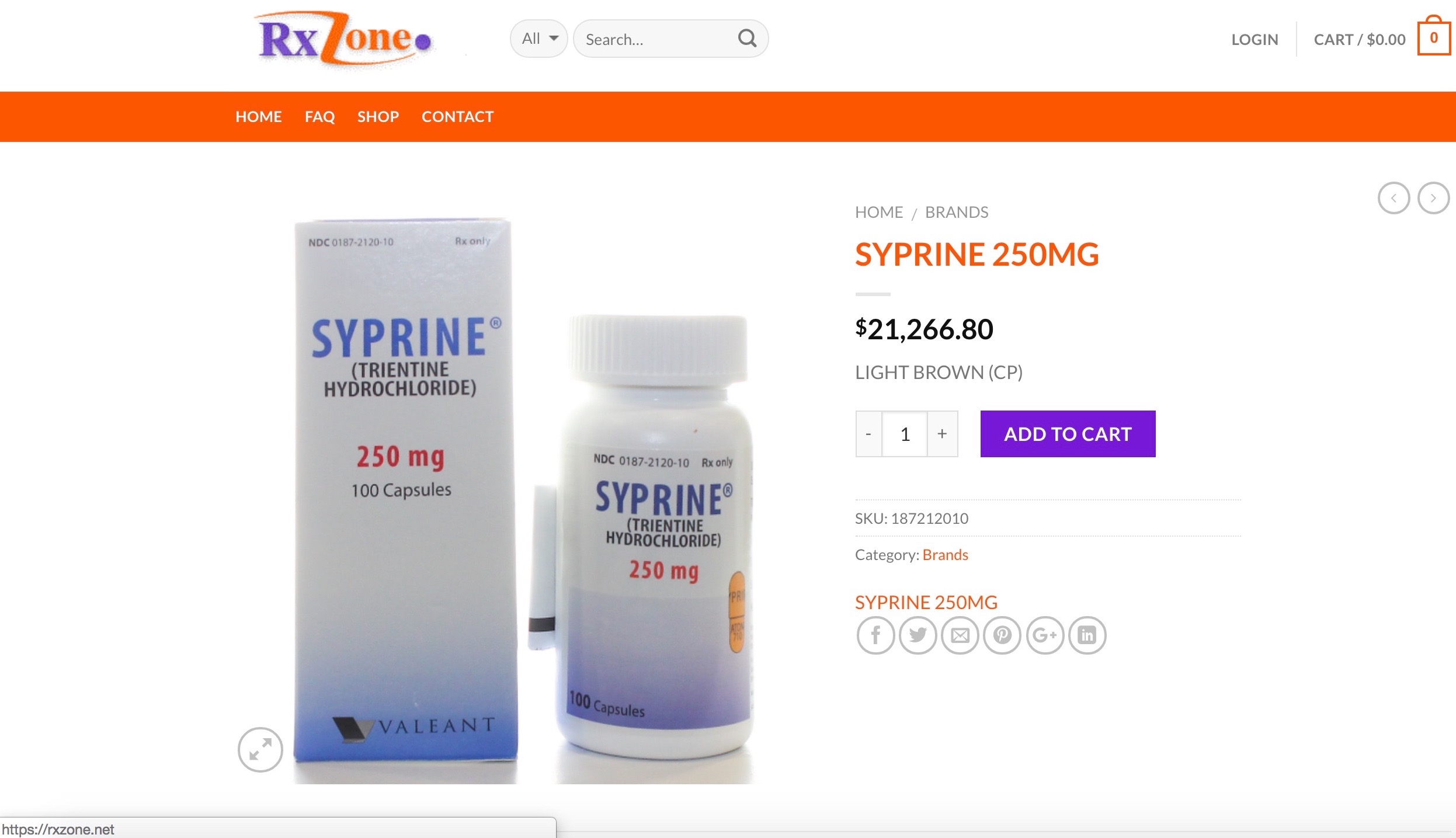

Valeant Pharmaceuticals (now Bausch Health) acquired the rights to Syprine in 2010 and began increasing the price. It’s an old drug that was developed in the 1960s by British physician Dr. John Walshe, who made it in his laboratory and distributed it for free for many years. “It was cheap to make,” he told me. The generic name for it is trientine.

As a librarian at the College of William and Mary in Virginia for 34 years, Berna had good health insurance and drug coverage. Her WD went undiagnosed for 60 years, making her one of the oldest patients to be diagnosed. The first sign of her disease was cirrhosis of the liver that was picked up incidentally by a radiologist.

Upon retirement, she was insured through Medicare and supplementary insurance.

“By 2014 my projected co-pay exceeded $10,000 per year with my insurance paying over $260,000,” Berna testified. “That is untenable. Something has to be done.”

“I left the hearing feeling hopeful, and anticipated changes by Valeant,” Berna told me. “It’s very disappointing. It’s the same old, same old.”

At the hearing, Valeant executives expressed regret and admitted to being too aggressive with their pricing strategies. When questioned by Senators, they said they’d lower their prices.

For three years, Berna has waited. But Bausch Health has yet to lower prices.

“I left the hearing feeling hopeful, and anticipated changes by Valeant,” Berna told me. “It’s very disappointing. It’s the same old, same old.”

Therapist kept patients out of the system, but drug company put her in it

Rose was completing her college degree in mechanical engineering when she noticed that she drooled while reading. Then she began forgetting math formulas, so she’d write them on her arm. As a straight A-student, she was bewildered that she had to re-read book chapters because she forgot what she’d read. She was on the crew team, but her fatigue got so bad that she couldn’t keep up.

“I left college and went home,” said Rose, who asked that her name be changed for privacy. After seeing more than a dozen doctors in New York and not getting a diagnosis, she went to an ophthalmologist who told her that some diseases can be diagnosed through the eye. He was right; an exam revealed Rose had rust-colored rings in her eyes, known as Kayser-Fleischer rings which are commonly seen in WD patients.

Once diagnosed, Rose began taking the de-coppering drug, penicillamine. Her condition improved and she returned to college. But her WD left her with some memory loss and she couldn’t remember her calculus formulas. She switched majors and got a degree in occupational therapy.

Rose moved to Arizona and worked full-time as an occupational therapist for 20 years.

“As an occupational therapist I was contributing to the system, and keeping others out of the system,” said Rose. “Then the drug company put me into the system.”

“Then one day I went to the pharmacy to pick up my WD drugs and was told my co-pay was $12,000! I was a single mom raising two kids and I couldn’t afford it,” said Rose. “I felt totally screwed.”

She had been prescribed Cuprimine, the brand name version of penicillamine — also made by Bausch Health. Penicillamine was discovered in 1955, also by Dr. John Walshe. “It’s easy to make if you’re a good chemist,” Dr. Walshe told me.

Rose tried zinc supplements, an inexpensive, alternate treatment for WD, but they made her violently ill. Without her daily dose of Cuprimine, her fatigue returned and depression set in. She could only work part-time, so she lost her health insurance. Her WD symptoms worsened, so she could no longer work and applied for disability benefits.

“As an occupational therapist I was contributing to the system, and keeping others out of the system,” said Rose. “Then the drug company put me into the system.”

Importing drugs from Canada and overseas

After going without medication for months, Rose’s uncle found a way for her to get affordable penicillamine through a Canadian pharmaceutical broker. At first, her supply came from England. “The medicine looked and smelled like what I had taken for years, although the brands were different,” said Rose. “But then a shipment came from India that didn’t smell right.”

She looked for another option and found Duane, a prescription drug broker in the Midwest who could get her drugs shipped directly from Australia. She needed a doctor’s prescription and paid about $200 for a three-month supply.

“We operate in a loophole,” Duane said. “Individuals are allowed to bring in a three-month supply of prescription drugs from other countries.”

What Duane told me is partly true: It’s illegal for individuals to import prescription drugs in most circumstances, because the FDA can’t ensure the drugs’ safety. And anyone who facilitates the importation is also liable. But in reality, the FDA looks the other way.

So, it’s tempting to take the risk. Duane imports an AIDS medication for a client who had a $25,000 co-pay. “I can get it for him for $1,200 a month.”

With exorbitant drug prices and patients’ growing inability to pay them, there’s momentum to make such drug imports legal. Five bills are before Congress that would allow prescription drug imports, primarily from Canada.

Staying at poverty level to get prescription drugs

Ashley Williams was about to start classes at Kansas State when she was diagnosed with WD and had to quit school to go to work instead. She was grateful to have a diagnosis for the hospitalizations and unnecessary surgeries she experienced the previous two years.

“I needed health insurance, so I took a full-time job with a technology company,” said Ashley. “I worked my way up from ‘coffee girl’ to project manager and was working 70-80 hours a week.” Even though she was taking Syprine, her health deteriorated. She thinks it was due to working too hard, to prove she wasn’t sick.

For medical reasons she got laid off and applied for disability benefits. Now with Medicare and supplemental insurance to cover her health care, she can’t afford her Syprine co-pays.

“This year, I was told that the funds for Wilson disease were already gone!” said Ashley. “The $1,200 co-pay for my 30 days of trientine took my entire Social Security check.”

“A health insurance broker advised me to look into the PAN Foundation,” said Ashley. “I qualified and get $10,000 a year to cover the cost of my co-pay.” The Patient Access Network Foundation relies on donations to help people who are underinsured with medication costs.

Patients have to reapply every January for the PAN Foundation’s drug benefit. “But this year, I was told that the funds for Wilson disease were already gone!” said Ashley. “The $1,200 co-pay for my 30 days of trientine took my entire Social Security check.”

Teva Pharmaceuticals introduced the first generic trientine in 2018 to compete with Bausch’s Syprine.

Generic competition hasn’t lowered the drug cost… yet

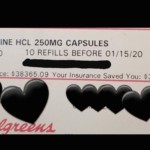

Dawn, who was diagnosed with WD at age 37 after her liver failed, was shocked when she picked up her prescription for trientine in January. The list price was $38,365.09. Her insurance co-pay was only $15.

Still, she’s not taking her good fortune for granted, and is stockpiling her drugs.

“I’m scared to take them all,” said Dawn, who asked that her real name not be used. “I went without my drugs for three years because we couldn’t pay for them when the costs spiked.”

Ultimately, the drug saved her life. But they went bankrupt in the process.

Her husband had taken a new job just before she was diagnosed with WD. And then, just as their new insurance was coming through, “the suckers fired him,” Dawn says. “They knew I needed a liver transplant and was really sick.”

She had no choice but to take Syprine, and ultimately, the drug saved her life. But they went bankrupt in the process.

Bausch currently offers patient assistance programs to insured and uninsured WD patients in the US who need Syprine or Cuprimine. “Our first priority is that every patient has access to the medicines they need,” a Bausch Health spokesperson said in a statement.

Dawn tried to get help from the drug company previously, but couldn’t. The inexpensive alternative, zinc therapy, made her sick.

Her husband eventually found a job that provided health insurance — 700 miles from their home, in another state. “He works 70 hours a week hauling chemicals in extreme weather on treacherous roads. It aged him so much.”

Dawn’s liver healed enough so she could be taken off the transplant list. Still, she’s furious with the drug company for making the drug’s cost out of reach for three years. And, she’s fearful it could happen again.

How does the tale end for the 4 women?

Berna Heyman is encouraged that the problem of high drugs costs is still a major discussion. “That’s the bright side,” she said.

However, since she was forced to switch her WD medication, tests show copper has reaccumulated in her liver. Her doctor advised a low-copper diet for several months, but that didn’t help. “I may have to start taking trientine again.”

Rose credits Duane for saving her life with the drug imports. But fear of her supply line drying up led her to enroll in a clinical trial testing a new drug for Wilson disease so she can get her life-saving medication at no cost for the next five years. “I hope the new drug works,” she said.

Fear over the uncertainty of being able to pay for her drugs also led Ashley Williams to enroll in the new WD drug trial. By chance, she was put in the “standard of care” arm of the trial. That means she continued on trientine for a year and paid the drug’s cost. “Starting in April, I will be taking the new study drug,” she said. That means she pays the $1,200 co-pay for her trientine for another month.

“It’s scary to think that I have to stay in a drug trial to get my medication paid for,” Ashley said.

Even though Syprine saved Dawn’s life, she’s fearful that the drug’s cost could make it out of reach for her again. Her solution: Rationing her drugs.

Perhaps this will be the year that the Wilson disease drugs Dr. John Walshe discovered and developed more than 50 years ago will be affordable again. But, the human toll and cost to society that the drugs’ price spikes caused, remains.